The Economics That Decide AI Growth or Crisis

“Sustainable intelligence is about circulation.”

If an AI crisis does come, what are its fundamental drivers? And how much could investors lose when it arrives?

These aren't hypothetical questions. The market is flashing contradictory signals: margin debt has reached levels only exceeded in February 2000, while companies slash tens of thousands of jobs despite record AI revenues. Mass adoption, value concentration, minimal redistribution.

For AI entrepreneurs and investors entering now, this pattern implies significant financial risk.

To understand the fundamental drivers—and quantify potential losses—let’s start with a simple model that reveals what happens when a company captures value but lacks redistribution capacity.

A toy example

Imagine a tiny world with just ten people, each holding $100. That's the entire money supply: $1,000 total.

Now a company (or a group of companies) appears with a product everyone loves. Each year, people happily pay 10% of their money for the service. The company collects the money and keeps it — every dollar extracted simply vanishes from circulation.

Stage 1: The golden beginning

This looks like the perfect business. When the user base grows from 1 to all 10 people, the revenue grows from $10 to $100 (10% from each of the ten people) per year.

Using a standard 30× revenue multiple, the company achieves a valuation of $3,000. When revenue is strong, investments flow in with optimism.

Stage 2: The slow drain

But there's a problem: without redistribution capacity, people get poorer by using the service.

After the first year, the ten people each have $90 remaining. The total money supply outside the company shrinks to $900. The next year, the company collects 10% of this remaining supply—revenue falls to $90, and valuation drops to $2,700.

Here’s the full trajectory:

| Year | Each Person Has | Revenue | Company Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | $100 | — | — |

| 1 | $90 | $100 | $3,000 |

| 2 | $81 | $90 | $2,700 |

| 3 | $72.90 | $81 | $2,430 |

| 4 | $65.61 | $72.90 | $2,187 |

| 5 | $59.05 | $65.60 | $1,968 |

After five periods, the people’s assets are down to $59 each. The company has drained $409 out of the original $1,000 money supply. Its valuation has fallen 34%, from $3,000 to $1968.

This is the simplest example showing how a company's success may erode the very foundation its valuation rests on when lacking redistribution capacity. A useful and well-adopted service turns into a lose-lose situation for both users and investors.

Stage 3: When leverage triggers

Now let's add a realistic twist: leverage.

Not all investments can bear the slow drain forever. Investors who borrowed money to buy shares at the peak valuation of $3,000 face margin calls as the stock falls 34%. Forced selling begins.

Suppose 50% of shares are triggered and must find buyers. But only $591 ($59.05 per person) exists in the money supply. The highest possible valuation—assuming everyone uses their entire savings to buy—becomes:

$591 ÷ 0.5 = $1,182

This represents a 61% collapse from the peak, and the actual valuation could be even lower if:

A higher percentage of shares must be sold

Only a portion of the remaining money supply is willing or able to provide support

Panic selling accelerates the decline

Why AI companies are different

To understand whether the toy model's dynamics apply to real AI companies, we need to examine how value traditionally recirculates through the economy.

Traditional companies redistribute value through several channels:

Employment: Wages flow back into the economy

Supply chains: Payments to vendors and partners

Dividends: Returns to shareholders who spend

Taxes: Government spending recirculates wealth

AI companies can operate with dramatically less redistribution:

Minimal labor requirements (high revenue per employee)

Minimal supply chain breadth (AI does it all)

Concentrated (and circular) ownership structures

Infrastructure costs that flows to its own share-holding tech firms

When traditional companies adopt AI solutions, the re-distribution gap widens: more labor layoffs, and less supply chain reliance.

This doesn't mean AI companies create no value or that displacement is guaranteed. It means the rate of value extraction well exceeds the rate of redistribution—at least temporarily now.

Market signals

Now that we understand the mechanism and why it applies to AI companies, we can interpret what the market is telling us. The signals are contradictory but revealing:

Signs of exuberance:

Margin debt relative to money supply has reached levels only exceeded in February and March 2000

Massive circular investment deals among OpenAI, Nvidia, Microsoft, and Oracle, with each company both investing in and purchasing from the others

AI capital expenditures accounting for 1.1% of GDP growth in H1 2025

AI stocks representing 75% of S&P 500 returns, 80% of earnings growth, and 90% of capital spending growth since ChatGPT launched

Nearly two-thirds of U.S. venture deal value now flowing to AI startups, up from 23% in 2023

Signs of contraction:

On-going layoffs: Amazon cutting over 30,000 positions; UPS eliminating 48,000 employees; Meta dismissing 600 AI researchers.

Widespread adoption of AI accompanied by workforce reductions across sectors

The pattern matches our model: value concentration at the top, extraction without redistribution, and a shrinking money supply among potential customers and workers. The circular investment deals are particularly telling—when the same firms are both investors and customers, the appearance of growth may mask an underlying contraction in the broader economic base.

The reality

In our toy world, the extraction paradox is obvious: a company can't be worth more than the money available to sustain it.

In the real economy, complexity masks the same fundamental constraint. Money creation, international flows, and government intervention can delay the reckoning. But they can't eliminate the underlying arithmetic.

For investors and entrepreneurs, this suggests that business model design—specifically, how value flows through the ecosystem—is as important as the value created.

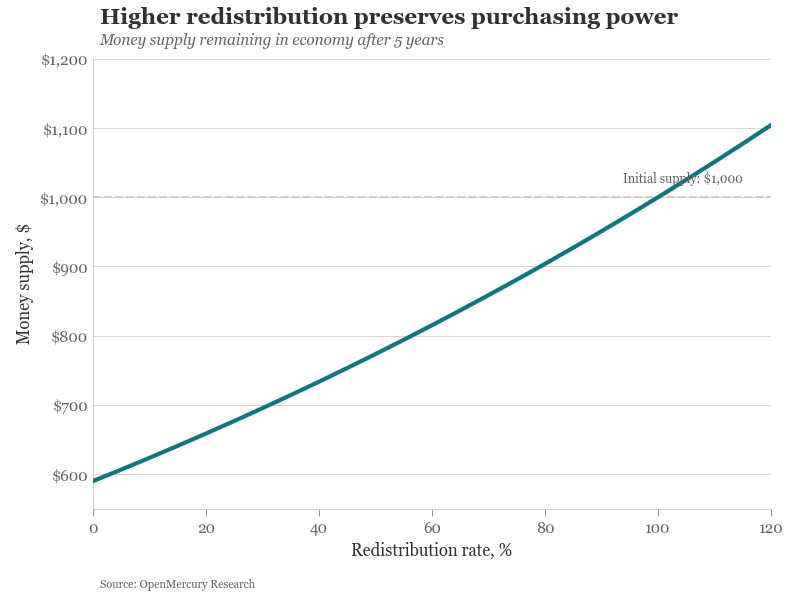

What redistribution changes

Back to our toy model. What if the company had redistribution capacity? What if each dollar extracted found its way back into circulation through wages, supplier payments, or other mechanisms?

The math changes completely.

With 50% redistribution, user wealth drops to $77 instead of $59 after five years. With 90% redistribution, it barely declines at all—hovering near $95. The money supply stays healthier, preserving the economic foundation that supports company valuations.

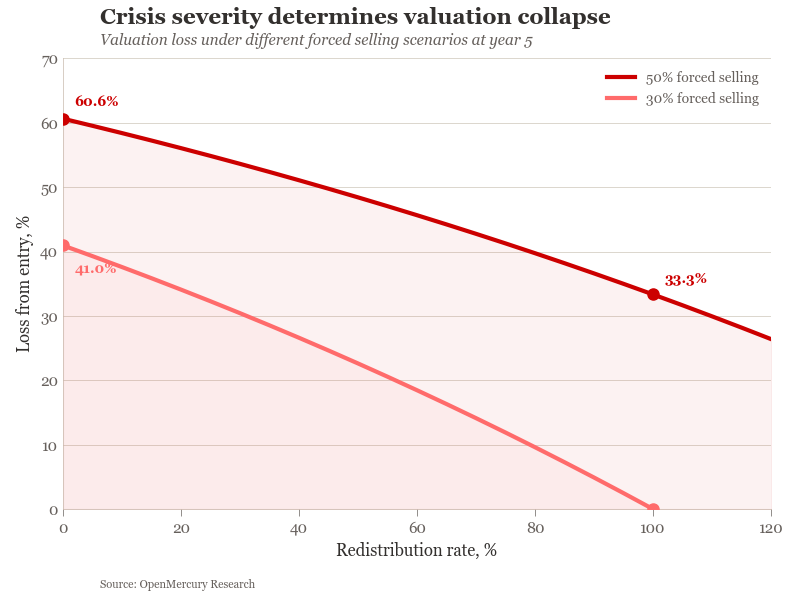

This translates into dramatically different crisis scenarios.

Let's run the same leverage situation—but compare outcomes across different redistribution rates. Remember, we're assuming a certain percentage of shares must be sold due to margin calls, and the only available money to buy them is what remains in the money supply.

**Mild crisis (30% forced selling):** A fully redistributed company experiences no losses from entry valuation, compared to 47% losses for a zero-redistribution structure. The difference: 47 percentage points of protection.

**Severe crisis (50% forced selling):** The gap widens further. Zero redistribution leads to catastrophic 61% losses, while full redistribution limits damage to 33%—still painful, but survivable.

Higher redistribution rates preserve both user wealth and company valuations, creating a more stable economic base. Moving from zero to full redistribution cuts potential losses nearly in half, even in severe crises. What could reduce the risk?

This isn't just an academic exercise for us. It’s part of our mission.

At OpenMercury, we believe the solution requires both technology and structure. We're biased—we're building in this space—so take our proposed solutions as hypotheses to test rather than proven answers.

Technology design: attribution

Right now, AI creates enormous value but we can't track who contributed what. When an AI model generates $1 billion in value, where did that value come from? The users who provided training data? The creators whose content was used? The customers whose usage improved the model?

Without attribution, value flows to whoever owns the infrastructure—creating extraction without redistribution. The money concentrates. The paradox begins.

But if AI systems could track value contributions precisely—crediting creators when their work improves models, compensating users when their data generates revenue, attributing developers for their specific contributions—the extraction loop becomes a circulation loop. The same technology that created the concentration problem can solve it, if we build attribution into the foundation.

Structural alignment

The other fix is financial structure—capital systems that enable value to move in both directions.

The systems that will endure are the ones that align capital with contribution, where the flow of investment and the flow of value reinforce each other rather than compete. In those architectures, every outflow has a corresponding return path. The economy breathes. Circulation replaces extraction.

A different capital structure is needed—less linear, more reflexive. Value doesn't pool at the center; it recirculates through the network that created it. For many AI companies, building new products won't solve the revenue problem. New economic architectures are required.OpenMercury is an AI company with roots in both AI and finance. We design attribution and redistribution technologies that align innovation with real economic value — building systems that strengthen, rather than strain, the foundations of growth. Contact us to get involved.

Suggested Citation

For attribution in academic contexts, please cite this work as:

Liao, S. (2025). The economics that decide AI growth or crisis. OpenMercury Research.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, or professional advice. You should not rely on this material for making investment decisions. Always consult a qualified financial advisor before making any investment or financial choices.